Muhammad’s Education and the Enlightenment

Before drifting out to sea and being carried away to Algiers by the Dey’s corsairs, Muhammad, then Ettore had already acquired an education in what would today be characterized as street smarts. We learn in Book One of the series how he grew up in the brothel in which his mother died giving birth to him. Finding himself at an early age averse to manual labor, he used his powers of retention to become a guide to tourists and pilgrims. He learned all he could about the Cathedral of St. Andrew in his native Amalfi, memorizing details about the paintings, sculptures and architectural features of the Cathedral, and even more about the Saint for which it was named. As a guide, he came into regular contact with tourists from all over Europe and, again, his powerful memory enabled him to acquire several languages and dialects.

Much of this is available online at: https://thewritelaunch.com/2019/01/adrift-and-at-risk-guide/

We learn, too, in Book One that Ettore was careful with his earnings, hiding coins in strong boxes he hid behind loose bricks in the kitchen. We also learn that he was not above deceiving his partners when opportunities to earn more came along. The last such opportunity, borrowing old Grigio’s skiff, led to the disaster that brought him to Algiers. The first of many disasters with silver linings that characterized his life of adventure.

We learn throughout the books of the series, that Muhammad retained memories of what he’d learned or intuited in the brothel. By way of example, in A RUNAWAY IN ALGIERS, he recalls:

My ‘mothers’ at the House of Beautiful Swallows in Amalfi chastened me more than once in my youth for masking with exaggerated humor my propensity for amplifying the things that irritate me. It is ‘unmanly’ they told me, those forthright and outspoken ladies of the night who raised me as their own.

“And how,” I remember asking them, “would you know what is manly or unmanly?”

To which their reply had been laughter of the knowing sort. Peals of laughter.

And, in A GRAVEYARD IN ALGIERS:

He is a handsome man, I find myself thinking, and I want to like him. To the Swallows, however, I sense his elegant and attractive appearance would make him another mark. I have to admit he has the look, the one the Swallows spoke of so knowingly among themselves and refused to discuss whenever I asked them to explain.

In AN ABDUCTION IN ALGIERS, Muhammad recalls:

I see myself, then, at the age of perhaps eight or ten, a young boy in short pants who thought he might one day be as wealthy and as fashionable as the men who frequented the House of Swallows only steps away from the Piazza del Duomo in Amalfi. I had been warned, repeatedly, about going upstairs at the great house after sunset, and told to remain in the kitchen to help with old Josephina until she sent me to sleep in my little hammock not far from the hearth there. One night I said good night to Josephina as usual and, when she left to carry a tray of cut melons upstairs, I filled my hammock with onion sacks and covered them over with the old apron I used as a blanket. Then I left the kitchen by the back door and crossed the street to the annex that housed the sisters of the Luna Convento when they needed to stay in the town center.

In their white wool and black cap attire, the sisters lived in a world altogether different than the one I inhabited, but I was certain that if I could find a way to the roof of their building, I might observe whatever was taking place upstairs at the House of Swallows.

Sometime later, though I succeeded in gaining the roof, and with great difficulty, I discovered there was no way to go back down again. In the morning, shivering and hungry, I had to decide between remaining there or calling out to, or otherwise bringing myself to the attention of, the Swallows next door.

I held out almost until noontime.

The sting that lingered from the paddling applied to my hind side by old Josephina was as nothing by comparison with the sights from the windows of the upper floor that linger in my mind even to this day.

But sting it did, that paddling.

Was it worth it? In the darkness, I ponder the question as I continue to struggle with the cords on my wrists.

When Ettore was ransomed by the Freedom Charity, he was provided tutors by his benefactor, Caid Jafar, the English renegade sea captain who ran the charity. For five years, the young man studied Arabic, Turkish after which he enrolled in the Ottoman Law College where he learned the classical Islamic disciplines. At the beginning of his studies in the Arabic language, he became acquainted with the Koran and succeeded in memorizing it in its entirety over the course of a single summer. In most cases, two to three years are required for such a feat. But in many instances, people have completed memorization in periods measured by months rather than years.

References are made throughout the series to Muhammad’s visits to his benefactor’s personal library, and the library at the law college. In doing so, I called upon my own experiences, particularly at the library of al-Qarawiyyin at Fez, the oldest, continuously-operating, degree-granting university in the world. As the character of Muhammad was to have originated in Italy, I also made him take a special interest in the works of Muslim jurists and scholars who lived in Islamic Sicily during the centuries in which African Arab civilization was ascendant.

The Eighteenth Century was also the time of the Enlightenment, a European intellectual and philosophical movement in which reason was understood as the means to dealing with humanity’s problems, with particular emphasis on the freedom and happiness of the individual. It was during this period that society began to be thought of as a social contract between rulers and those they ruled. While Caid Jafar espouses some of these ideas, Muhammad Amalfi gravitates toward legal reform along the lines articulated by Cesare Beccaria in his work, ON CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS, first published in 1764. In the interests of keeping the stories moving in the novels, I resisted the temptation to make outright comparisons between the Ottoman/Algerian and European systems of law, politics and society. Nonetheless, the careful reader will undoubtedly note the attitudes and thinking reflected in Muhammad Amalfi’s words and deeds throughout the series.

While I have made use of dozens of classical Arabic works of Islamic Jurisprudence in depicting Muhammad Amalfi as a student of the law, I should like to mention Allan Christelow’s MUSLIM LAW COURTS AND THE FRENCH COLONIAL STATE IN ALGERIA, which, though it treats the colonial period, nonetheless includes a valuable chapter on The Geographical and Historical Context and the Lines of Institutional Change. The chapter, and much of the book, sheds a good deal of light on the legal system during the Ottoman Regency in Algiers and the varying social patterns between the Eastern and the Western areas of Algeria. In English, I’ve also made use of EBU’S-SAUD, The Islamic Legal Tradition by Colin Imber and STUDIES IN OLD OTTOMAN CRIMINAL LAW edited by V. L. Menage. Though, as I alluded to earlier, the main source is the corpus of classical fiqh literature in Arabic; particularly the works of the Maliki and Hanafi schools representing the choices of the populace in historical Algiers during the Turkish Regency. As a sort of honorable mention, I’ll list Abdullah Kannun’s Arabic work entitled ADAB al-FUQAHA as a quick reference to the fiqh of the Maghreb.

As a footnote to the discussion of the European Enlightenment, if I hadn’t taken the opportunity to voice my own admittedly biased and decidedly uninformed opinions on the matter. The Maghreb during the period of the Eighteenth Century was busy fending off the repeated attacks of Europeans desirous of increasing their trade with the East and the countries on the shores of the Mediterranean. (Remember how North Africa, with its several growing seasons, had for centuries acted as the bread basket of Rome; or how Algiers staved off hunger in France during the Revolution!). In this effort the enlightened European politicians were assisted by the clergy they disdained by weaponizing their prevailing attitudes of ignorance and fanatical adversity to Islam and Muslims.

A treatise of interest on the subject of European intentions to maintain their dominance in Mediterranean trade was written by a Venetian merchant lobbying for cooperation with the Maghrebi states late in the Eighteenth Century. This was entitled, in translation, A Treatise regarding the System of War and Peace as Practiced by the European Powers with the Barbary Regencies. I found the original Italian on Google Books, and it’s an eye-opener. I only wish my Italian was up to a decent translation of the same. The treatise ends this way:

On you, Nations of Europe, rests the choice… the point of a sword? Or an olive branch?

And why wouldn’t the Muslims of the Maghreb look askance at the European experiment with reason and the social contract? They, too, could see how Voltaire and Rousseau died in bitter disappointment. The French couldn’t very well keep the events of their revolution, with its reign of terror and the invention of the guillotine, quiet. To Muslim observers the incredibly profitable North Atlantic slave trade was no secret, even as it prospered and grew during the Eighteenth Century. The French Revolution’s profession of equality, brotherhood and liberty was an empty slogan in view of the revolutionaries’ failure to close down the slave trade or liberate the hundreds of thousands of slaves in French territories, especially on the sugar plantations of the West Indies. Throughout, the Europeans continued to heap calumny on the Muslims of the Maghreb for their enslavement of Europeans. While I cannot condone any of that, I can certainly point out that the numbers tell the real story.

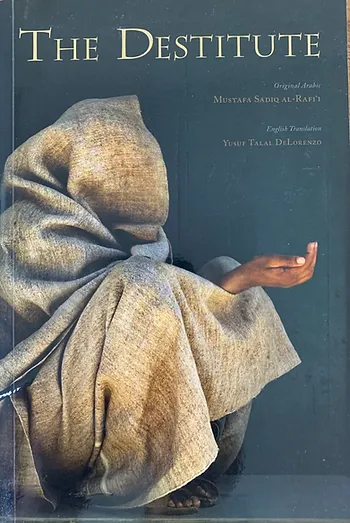

Should anyone imagine that changes occurred in the North African view of European humanity as represented by the Enlightenment, then let them consider the colonial depredations, lasting well into the Twentieth Century, of the French in Algeria and elsewhere on the African continent. Then, add to that the cruel exploitation by the Italians, Belgians, Germans, Dutch and English after the Portuguese had had done with their atrocities in Africa and Asia. For those interested in the Egyptian perspective on Europe during WWI, when the Europeans proved with blood and thunder their inability to live up to their own ideals, you may want to see my translation of Mustafa Sadiq al-Rafi’s THE DESTITUTE. If Muhammad Amalfi looked on occasion at the legal reforms suggested by Cesare Beccari, he did so with an eye toward improving the Ottoman-Algerian system of justice, not replacing it.

In the West, one might observe, almost callously, the response to the bloodshed of WWI was the Roaring Twenties. While in the Middle East and North Africa, and in Asia, the real and lasting hardships brought about by the bloodshed in Europe occasioned disenchantment, reassessment and a gradual search for identity that eventually, and one might say logically or illogically, led to a disastrous return to literalist religious fundamentalism. Until and unless we come to realize how all of us are in this together–everyone on the planet–we’ll continue to see misery in the form of famine, starvation, inequality, despotism, burgeoning refugee populations, and wars.

هذا ما عندي، والله أعلم بالصواب، وهو ولي التوفيق والهداية!